Throughout several days in the end of June, over 20 ships reported problems with GPS reception in the Black Sea. According to experts, the problems were probably a result of an attack on the GPS infrastructure.

August, 2015

A handful of people are sitting around a monitor at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (DRE). A red dot lights up, and locates us outside of Oslo in Norway.

We type a couple of commands on our laptop. Within minutes, the dot has moved to a university outside of Kasugai in Japan, moving in perfect circles around one of the buildings. The Google Maps app on our mobile phones is projecting the same position on the other side of the planet.

Two minutes later, the dot is back at its correct position.

The reason for this visit to the DRE was to test a system which can send spoofed satellite signals to most modern GPS receivers. Two years later, we’ve picked up the story again, as several episodes indicate that the technology is being used by military powers.

Most modern infrastructure is dependent on GPS, a system enabling high precision in both geographical positioning and timing. GPS is a great friend to have when you don’t quite know how to get where you’re going.

That’s what comes to mind for most people when they’re thinking about GPS. But in reality, it is one of the most important components of a modern society.

Plenty of sectors depend on GPS. Not necessarily the positioning itself, but the timing: Each of the Global Positioning System’s 24 satellites have their own atomic clock. This means that the time reported through GPS is one of the most precise available.

That might be useful if, for instance, you run a stock exchange, where automatic trading systems execute thousands of trades every second. A millisecond here and there might amount to differences of millions of dollars.

The same goes for mobile carriers, whose clients expect their calls not to be interrupted when moving from one cell tower to another. Cell towers largely depend on GPS for timing and synchronization.

But the GPS system is maybe even more vital to the need for positioning in marine traffic. Hundreds of ships travel through waters with no Vessel Traffic Service available, and few visual landmarks. Without GPS, navigating to the right harbour would be much harder.

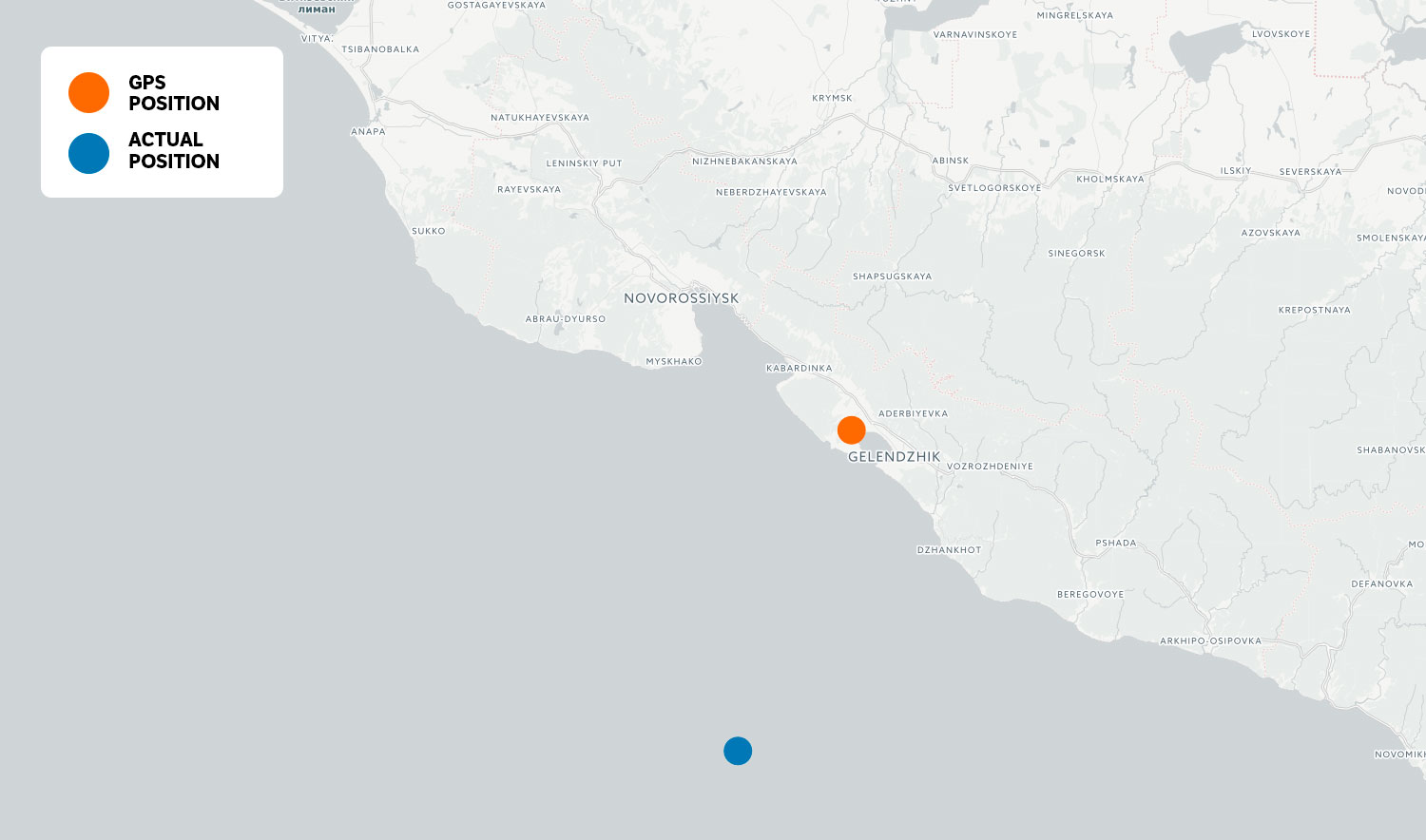

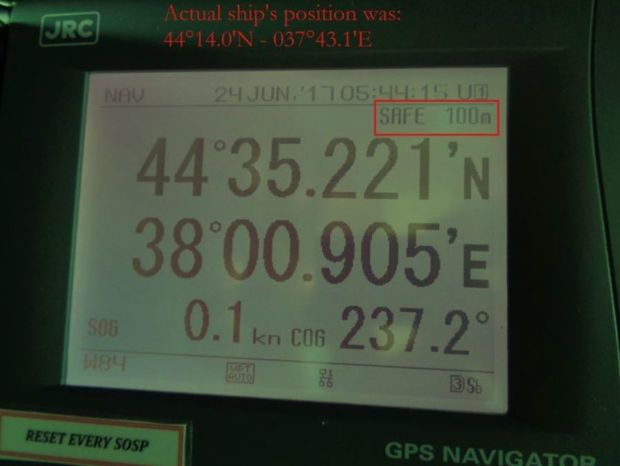

On 22 June, a ship in the Black Sea sent a report to the US Coast Guard indicating anomalies in the GPS system. The ship’s navigation system reported that it was on land, close to an airport in the Russian city of Gelendzhik. A couple of days later, over 20 ships gave similar reports in the same area.

Maritime Executive was the first publication to mention this story. In their article, there’s a quote from the exchange between a vessel and the US Coast Guard:

GPS equipment unable to obtain GPS signal intermittently since nearing coast of Novorossiysk, Russia. Now displays HDOP 0.8 accuracy within 100m, but given location is actually 25 nautical miles off

In layman’s terms: The captain is saying his GPS system is certain of its position within 100 meters, even though the actual position of the ship is more than 25 nautical miles from the position reported by the GPS.

NRKbeta has gotten access to all marine traffic in this area between 22 and 24 June from Marine Traffic, and we’ve identified 24 vessels who were affected by the spoofing attack. We have contacted several of the vessels. Two of them told us they know about the incident, but did not want to comment further. Both of these ships are owned by Russian entities.

The captain of the tanker Suez George did not know about the anomalies, but after we got in touch they went through their navigation logs and retrieved hourly positioning data for 24 June.

That data shows clearly that the Suez George is «transported» to the airport outside of Gelendzhik when it gets near the coast of Russia.

We have also gotten access to the detailed ship log from the Suez George. This shows pretty clearly that the GPS receiver aboard is sent spoofed signals several times when the vessel approaches the coast. The timeline animation below shows the ship’s position on the 21 and 22 June:

From time to time, the ship is back to it’s actual position, even when it’s close to the coast. This can indicate either that the transmitter has been temporarily turned off, or that the spoofers are experimenting with the functionality of the equipment.

– The evidence points towards a «spoofing attack»

In the tiny world of GNSS research – a general term for satellite based navigation systems – Todd Humphreys is a household name. He is a professor at the University of Texas, and has used large parts of his career doing research on satellite based navigation.

In 2013, Humphreys did an experiment where the luxury yacht White Rose of Drachs was led from it’s actual position by several kilometers. Neither the crew nor the navigation systems on board were able to notice the anomaly.

Since GPS relies on satellites more than 20 000 kilometers above the Earth’s surface, signal strength is quite low when it reaches the Earth. If someone has a transmitter in close proximity to the area you’d want to spoof, overpowering the GPS signals isn’t very demanding. This is called a spoofing attack.

In an email to NRKbeta, Humphreys writes that he is pretty certain that this is a spoofing attack:

– The evidence points strongly to a spoofing attack. The captain’s account and the pictures he sent are quite convincing. And according to my sources it’s still ongoing, but at a lower signal strength, Humphreys writes.

There have been episodes close to the Kremin as well, where tourists have reported that their mapping apps report that they are at an airport when getting too close to the fortified complex. Humphreys has a theory that this is an effort to keep drones from flying in the area:

Several of us [researchers in GNSS] have concluded the Kremlin spoofing was likely trying to trigger UAV geo-fencing, which prevents UAVs from flying near airports.

Todd Humphreys

On the ground in Moscow

We got in touch with NRKs Moscow correspondent, Morten Jentoft, and asked if he could investigate if this was still going on. We got a short video back, where he shows that his cell phone indeed shows the wrong position when getting too close to Kremlin. Video in Norwegian, with English subtitles:

Here is a photo from Jentoft’s phone, which is taken at a gallery near the Kremlin. As you can see, it is tagged at Vnukovo International Airport, an airport more than 40 kilometers away.

Jentoft says that these GPS-problems in Moscow only tend to occur when Putin is in town.

Several of the ships that were affected, were moving outside of Vladimir Putin’s Black Sea Residence when they were transported to Gelendzhik. In other words, this indicates that Russian authorities are doing GPS spoofing wherever the Russian president is located.

Humphreys concurs:

– It’s long been assumed that Russia, China, and other nations (including the U.S.) have the technology to carry out a spoofing attack. What’s surprising is Russia’s willingness to use it openly and somewhat indiscriminantly. It does fit nicely into what has been called Russian disinformation technology.

Putin was in this area when the spoofing incidents happened, inspecting the work being done on the natural gas pipeline Turkish Stream.

Experts have long believed that military powers have had this technology, but this is one of few episodes where the technology has been used at scale.

– Could cause physical and economic harm

In an email, Humphreys writes that this kind of spoofing attach can have devastating consequences:

They could cause physical and economic harm by undermining the trust we place on our navigation and timing systems. Were a state actor to target the English Channel, for example, they could cause great confusion and alarm with a GPS/GNSS spoofing attack.

Todd Humphreys

Democratization makes attacks easier

The difference between the attach in the Black Sea and the one NRKbeta did at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, is mainly a matter of signal strength. Spoofing a GPS signal over several miles, you’d need a transmitter and an amplifier located at an elevated point. Humphreys says that is quite easy:

– A spoofing device, a transmitting antenna, and a large amplifier is really all you need to do an attack like this. Wide coverage is achieved by mounting the antenna on a hilltop or tall tower.

One of the reasons it’s gotten easier to transmit information on a wide variety of radio frequencies, is because software defined radios have gotten cheaper. For less than $300, you can purchase the HackRF One, which can transmit on frequencies between 1 MHz and 6 GHz. That covers most of the modern radio spectrum, including the frequency used by GPS.

We used an HackRF One and open source software widely available online to simulate GPS signals.

Our experiment showed that most receivers jumped on our spoofed signal when the transmitter was turned on.

We analyzed the GPS frequency with a spectrum analyzer. The amount of information on the frequency is more intense when the spoofer is turned on.

– No knowledge of spoofing in Norway

Einar Lunde, Director of the Networks Department at the Norwegian Communications Authority, says they have no knowledge of illegal transmission of GPS signals in Norway. On a general basis, he says it’s important to have general knowledge of these technologies:

On a general basis, you can assume that equipment that enables these kind of attacks is getting cheaper and more available. It is therefore important to have knowledge of these technologies.

Einar Lunde, Norwegian Communications Authority

When we ask whether Lunde sees GPS spoofing as a potentially dangerous issue for autonomous vehicles, he writes that it’s important that manufacturers design their systems to be able to withstand errors and anomalies in the many available GNSS systems.

He is also quick to point out that transmission of GPS signals is illegal.

Spoofing detection

There is quite a lot of effort being put into technology that can withstand spoofing. Spoofing detection already exists, and is implemented in several of the new GPS receivers from suppliers like Broadcom and U-blox.

But there is a big difference between being able to withstand spoofing, and detecting it. If a GPS receiver detects spoofing it still won’t be able to show you the actual position, since the signals from the spoofing unit is closer and more powerful than the actual GPS signals.

Withstanding spoofing is also a costly affair. According to Todd Humphreys, the most promising techniques use several antenna elements to create reception beams in different directions, nulling out the signals from the spoofer. This will work as long as the spoofer is transmitting from only one or two locations.

For cell phones and other products where physical space is an issue, spoofed GPS signals might still be a problem for years to come.

NRKbeta has asked the press contact at the Russian Embassy in Oslo to comment on whether the attack is done by Russian authorities, but they say this is outside their area of responsibility. We have asked the press contact to relay our questions to relevant authorities in Russia, but at the time of publishing we haven’t received further information from the Russian Embassy. The article will be updated as soon as we receive comments form the right authorities.

[…] from the Black Sea points towards a co-ordinated attempt to disrupt GPS. A recently published report from NRK found that 24 vessels appeared at Gelendzhik airport around the same time as the Atria. When […]

[…] from the Black Sea points towards a co-ordinated attempt to disrupt GPS. A recently published report from NRK found that 24 vessels appeared at Gelendzhik airport around the same time as the Atria. When […]

[…] the following couple of days, 24 vessels within the house have been affected, consistent with research by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. When the non-profit adopted up a month later, they discovered proof that GPS indicators have been […]

[…] we talked about setting up a GPS spoofing device inside of a Faraday cage, and thereby tricking Strava into thinking our device was actually at the […]

[…] (via GPS freaking out? Maybe you’re too close to Putin) […]

[…] Read the full article featuring Dr Humphreys. […]

[…] from the Black Sea points towards a co-ordinated attempt to disrupt GPS. A recently published report from NRK found that 24 vessels appeared at Gelendzhik airport around the same time as the Atria. When […]