If you’re asking me, The Daily is the best news format available today. But how can something based on yesterday feel just as fresh tomorrow? I think that’s actually part of the secret sauce. Let’s examine the sound of The New York Times more closely.

«From The New York Times, I’m Michael Barbaro. This is the Daily. Today.» prefaces a thorough walk through today’s most central topic in the US. Towards the end, you get a fast-forward through other headlines you need to be aware of, before it – around 23 minutes later – is wrapped up: «That’s it for The Daily, I’m Michael Barbaro. See you tomorrow».

You’ll now be familiar with the broader lines of a current issue, you’ll have a slightly firmer grip on a chaotic world, and the fuzzy feeling of time well spent.

The Daily has developed into a journalistic flagship, every day gracing the top of the NY Times frontpage – or for that part the upper regions of the podcast download statistics. Every weekday, a new episode is ready before 6AM NY time.

This moment demands an explanation. The Daily is on a mission to find it.

Tagline, The Daily

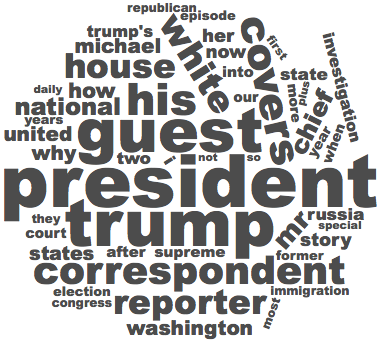

Making head and tails of the chaos of events taking place in today’s USA is demanding. 192 out of 413 The Daily episode descriptions feature the word «Trump».

And even when the turbulence surrounding the US president isn’t the main topic, The Daily is still mostly about the US – mirroring the US-centrism of US media in general. But you will also get the major developments in Turkey’s downhill slide towards dictatorship, or the situation for the Rohiynga people in Myanmar, to mention the two most recent foreign episodes when this was written.

During the August week I wrote this, several episodes covered the trials against Trump’s lawyer Michael Cohen, and campaign manager Paul Manafort – both playing pieces in Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian involvement in Trump’s presidential campaign.

What makes The Daily different?

Personally, I seldom read more than the first few lines of an online article, before I slip into skimming the text. But when listening to The Daily, twenty-several minutes further downstream I’ll often find myself disappointed that the episode is already over.

Why have I got this seemingly unlimited capacity to absorb information from The Daily?

I think it has a lot to do with limitations.

The specific limitations of The Daily shape what we hear, making it unique. Some of the limitations are generous, others quite confining. They all contribute to the final result.

Let’s examine the generous limitations first:

GENEROUS LIMITATION: The man himself

There is no escaping the fact that casting is playing a significant role here.

Local Boy Makes Good

The man in the white leather chair mentions his therapist in both of the meta podcasts I listened to researching this article: Inside The Times and Longform Podcast.

The script writer is r-e-a-l-l-y in love with the clichees, and have laid them on a tad to thickly while building the Barbaro character, would’ve been my first thought, if this was a film.

The cinema friendly script devices just keep on coming: Barbaro grew up in a small town in Connecticut. His debut in the media business was as a delivery boy for the local New Haven Register. On Sundays, the paper was so fat that one of the parents (either the fireman or the school librarian) had to drive the family’s Subaru station wagon with the hatchback open, as he and his sister delivered papers right and left. «I was delivering news to people, and I was the first person to see it.»

And then he worked his way up.

You’re fired!

No longer a rookie, Barbaro ended up doing political journalism in the New York Times, where he among other things followed Mitt Romney’s campaign in 2012, and Donald Trump in 2016.

Until Trump suddenly fires him on Twitter:

Michael Barbaro, the author of the now discredited @nytimes hit piece on me with women, has in past tweeted badly about me. He should resign

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 18, 2016

The Special Sauce

Towards the end of the campaign, Barbaro led the podcast The Run-Up, following the (as it says on the tin) run-up to the election. Here they eventually came upon a voice that was curious, generous, and took the listener by the hand through complicated things.

But more importantly: They managed capturing the intelligence, authority, and thoughtfulness of the NY Times reporters, and managed to transform that, and their real warmth, into audio. This is the Special Sauce, he tells the Longform Podcast.

Lights, camera, ACTION

During this year’s SXSW conference, I took a seat ringside to observe Barbaro and his technique more closely. You can learn a bit just from seeing him enter a room and start working. This is a short segment I shot on my phone:

Notice how quickly he (after briefly, but warmly greeting the around 1000 people in the room) shifts his attention to a journalist who might be less accustomed to the stage than he is, and how he is creating a safe and informal protective bubble around them.

Less than 40 seconds pass from the intro music fades until the guest – and the reason it is precisely her sitting in that chair – is introduced. We know what darker reality we’re about to enter. But we’ve already laughed 3 times in spite of the sombre topic. Now we’re on the edge of our seats, ready to continue our journey.

Michael Barbaro has a unique talent for hypnotising his audience together with his guests. Laughing, sniffling, amazed, shocked, we sit all the way through Rukmini Callimachi’s story about Syria and ISIS – until we emerge on the other side, slightly wiser.

Further on through the conversation I’m jotting down:

- the long interval between each time he opens his mouth, giving a lot of space for his guest

- long, precise questions are fencing the course of the conversation in

- engaged and prolonged listening – friendly waiting

- thick script – well prepared

- guiding the conversation onwards through small hints

- summing up, trying to lead us through analysis and interpretation

GENEROUS LIMITATION: The good specialists

Hosted by Michael Barbaro and powered by New York Times journalism.

The Daily is created within the New York Times. One of the larger news organisations in the world, with over a 1000 reporters. Many of the journalists are following single topics and stories over time – so called beat reporting. This means they have the insight both to sketch out the larger picture, and to fill in the details.

Times journalists are incredibly plugged in to what they do. It is their life’s work, a calling, not just a 9-to-5 thing they do, he tells the Longform Podcast.

But, in addition to being a strength, this deep familiarity with the material can also be a vulnerability: If you’re covering the same topic over a long period, you can end up assuming the public knows what you know, and that the basics aren’t needed.

A The Daily episode generally starts with a more or less blank slate, which is then filled. Barbaro is not after the story the journalist just wrote, but the bigger picture. And he has the courage to ask the slightly banal questions on our behalf. This ensures that the fundament, which can be self evident for the specialist, is safely in place when they together explore one single story with a depth, and hunt for explanations that’s both different and deeper than what a reporter could have shoehorned into an article.

GENEROUS LIMITATION: The will to invest in something new

If an American started subscribing to the New York Times about a year ago, s/he would have gotten a Google Home smart speaker thrown into the deal to be able to use – among other things – The Daily.

The Daily is most probably an important effort for the NY Times. Newsprint is at the end of its life cycle, and they need new, strong news products people can become habitual users of on new platforms.

There is large audience with 20-30 minutes to spare daily, and The Daily is a good fit for both earplugs and smart speakers – two usage situations where competition in the top segment is still fairly small.

One reason the sound market isn’t as oversaturated by news providers as the text internet or the TV market so far, is in part because the ad market for audio is immature:

In podcasts you’ll hear ads for mail services (!), newsletter providers (!!), and mattresses (!!!). The giants within alcohol, luxuries, cars, chain stores, airlines (or whoever the typical major advertisers are), are largely absent.

Content financing is immature, and media corporations that can afford to wait out the market for a few years are able to establish themselves early with little competition. The NY Times has decided to set aside a number of people to work on this – according to The Vulture, The Daily is currently made by around 12 producers, and typically two or three producers are working on an episode at the same time.

And – equally important – the Times’ best reporters prioritise contributing to The Daily within their busy workdays.

GENEROUS LIMITATION: It is not radio

I think more than anything it’s that nobody here had a legacy in public radio. We didn’t have old habits to unlearn.

Sam Dolnick, New York Times | Newsonomics: The Daily’s Michael Barbaro on becoming a personality, learning to focus, and Maggie Haberman’s singing | NiemanLab

NY Times is making a podcast, not radio (even though they made a deal for a radio edition earlier this year). That the content doesn’t originate in broadcast radio has an impact both on how The Daily is made, and how it is consumed.

Free length

Because it isn’t broadcast, it isn’t necessary for the episode to have a precise length to keep the schedule som the next programme can start on time, or to ensure that advertising isn’t squeezed out.

So the editors won’t need to cut down a central point, or fill the sausage with jabber or music to fill the time. The episode length varies with what needs to be said, and things will get the space they demand, but not more either.

Rich raw material

The fact that it doesn’t spring from broadcast also means that the recording situation can differ quite a lot from live radio, where what’s included in part is determined by what the participants happen to think of saying in the spur of the moment. They record a large amount of material – depending on the episode anything from 45 minutes to 5 hours – which is then edited and cut through the afternoon and evening until they are satisfied.

GENEROUS LIMITATION: It is a podcast

From an audience perspective, the most obvious difference between radio and podcast is that you are deciding exactly what you’re listening to, and when you’re doing it.

Which means that my The Daily (new episodes are available around mid day, Norwegian time due to time zones) often starts while I’m cooking supper, whereas another one’s is starting on the train journey home to Suburbia.

Room for longer, unbroken thoughts

If I had been listening to traditional radio while cooking, I would have started listening towards the end of one show, and then caught the start of a new one. This listening pattern (and the myriad similar, but not identical entry and exit points across the audience) is effectively limiting the length you can afford to spend on a single argument or piece of reasoning, and also how much common ground in listeners the programme creators can assume.

In a podcast, on the other hand, you can be fairly sure people did hear from the start, that they have have the fundament 15 minutes later, and that they are able to follow a longer train of thought. And if we can use myself as a measure, I’m also more than willing to jump 30 seconds back, if an important point should get drowned out by banging pots or loud boiling.

Outside impulses

This inherent support for depth – combined with the factor that many podcast creators hail from media with different conventions – has revitalised the audio format. As a consequence, podcasts often differ quite a lot from traditional radio.

GENEROUS LIMITATION: The right length

When you spend twenty-odd minutes discussing one single thing, you have time to draw the most important lines, go sufficiently under the surface for context to emerge, frame things within a larger picture, and do a few attempts at analysing why things are as they are.

At the same time, you’re not so meticulous that most normal listeners will fall off before it’s over, or will have to distribute their listening over several sittings. Also, you’re not going so deep that the larger picture is slowly drowned out by details.

As a bonus addition to the main story in The Daily, they often add this small tail mentioning other of today’s stories that you need to know about. This tightly prioritised list wrapping it up gives a sense of «now I know what I need to know, and can move on with my life.»

Limitations furthering creativity

But it isn’t all luxury. There are some very central limitations limiting The Daily that are just as defining for its shape and taste.

The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.

Orson Welles

NARROW LIMITATION: Yesterday’s news

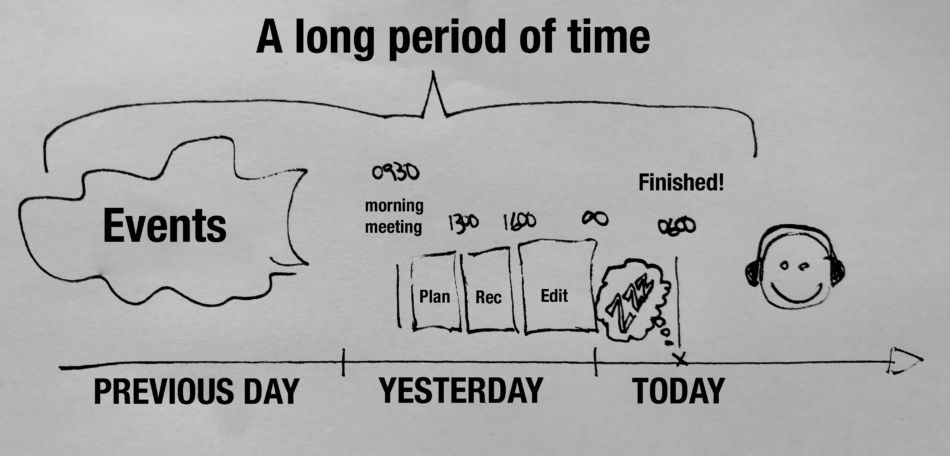

Work on the fresh episode of The Daily – the one that was stuffed into your Christmas stocking before 6AM NY time today – started yesterday at 9.30AM with the morning meeting in the newspaper.

In this meeting, the newspaper decided what would be covered, and how yesterday. Most of what they talked about would be stuff that had already happened the day and evening before that again, or that they already knew in the early hours would happen during the day.

This is the basis for the episode. And they will of course try to avoid making something that is past its Sell By-date the next day. This automatically excludes several topics and details that will change, surface, or evaporate during the day.

Leaving the morning meeting, The Daily are now forced to focus on the broader strokes when picking 1-2 stories to start working on. Then they’re spending up to 2 hours deciding how they’ll best tackle the story, and prepare for recording from 1 to 4PM. The editing follows. It will be a long day before the episode is ready, but they are usually finished between 7 and 9PM, Barbaro tells Newsonomics.

Illustration by Anders Hofseth NRKbeta

But this also leads to episodes that will last a few days in the fridge, if something extraordinary should happen. When the verdicts in the trials against Manafort and Cohen came within 2 minutes of each other, part two of a series on family separations at the US border had to wait in the wings for a couple of days.

This long lead time is automatically making The Daily a strong counter balance to so called Speed over Depth – one of the dynamics leading to media sometimes serving society poorly these days.

The Daily cannot be first, and that is also the reason they succeed in drawing the complete picture.

Speed Over Depth: Speed kills

Media’s tendency towards choosing Speed over depth is a larger problem than we’re aware of, according to Editor-at-Large of Vox Ezra Klein

We media are drawn towards covering what is now. What has conflict, and that everybody’s shouting about at the moment. This is happening at the expense of what is deeper, more important, slower, more difficult.

For Vox, who are on a mission to explain, the struggle to be first with the news is pushing them towards delivering faster than they’re able to process and understand the news themselves.

The Vox editor tells how difficult it is to not yet have an article up when the competition is out there already, and it feels like the audience is expecting you to be there.

The price we’re paying for an entire news business in the overtaking lane with main beams slicing the blood fog, is that the quality and the overview in the coverage disappears, and that more important topics are forced out by things moving fast. It is also making it easier for crafty players to take over the agenda.

Thanks to the underlying premises for how The Daily is made, the result is Depth over Speed. That means they’re both able to deliver on the deeper, more important, slower, more difficult stuff, and that because they’ve had time to build something more thorough, it is also a more satisfying listen.

NARROW LIMITATION: Lack of conflict

Unlike some other news formats, The Daily does not use conflict as a narrative engine. Primary sources aren’t in the room, and the host and the guest are on the same quest; they’re trying to understand a story.

This gives a different dynamic, feel and temperature than a news format with a source trying to tell a story using their own talking points, maybe withholding certain details, while the host is trying to crack their defenses with clever questioning to get at the answers.

That doesn’t mean that the journalist guest couldn’t well have been working hard to crack defenses and get at the story, but it will have happened prior to this, and outside this room. So we’re not in the midst of a clash of wills, but rather in a calm and explorative mood. It gives a more pleasant listening experience.

NARROW LIMITATION: There are no pictures

Another limitation and strength, is that the format is audio only.

Photos, video, and graphics are off limits, and everything needs to be presented and explained using spoken word and sound. Things are meticulously unfolded. Contexts and details are shown and analysed for 20 minutes, until the picture is relatively clear. That doesn’t mean we’re confined to the studio. Sound clips from key points of the story appear regularly, giving the story colour, nuances, and authenticity.

But because only the ears and the brain are busy, listeners have their hands free – to shave, have breakfast, go to work, fold laundry, or whatever their routine of choice is.

And this routine is probably central for the so-called stickiness: The way newsprint for years was kept afloat by being part of people’s everyday routines, The New York Times is apparently trying to position themselves within new routines in a more restless media reality, by being predictably present with a curious velvet voice that – together with some of the most well oriented journalists in the US – patiently tries to help us fathom.

For maybe all of these reasons, The Daily has developed into my main source for understanding what is happening in the world – or at least the US.

…and the sum is:

I am of course neither first, nor alone in discovering The Daily. It has maybe 5 million monthly listeners, and in media circles it has been spoken warmly of for well over a year.

Which is why offerings inspired by it is regularly surfacing. In neighbouring Denmark we’ve recently seen Politiken doing it. The effort is by all means decent. But on hearing it, you can’t help sensing the absence of the added weight of New York Times’ massive and specialised team of reporters.

Yet. Even though nobody would be able to fully reproduce it, I am still happily excited every time whispers are heard about different colleagues in Norway working on offerings inspired by Barbaro & co. As an audience, we can’t but look forward to it.

Also, it bears mentioning that since this article was initially published in Norwegian on NRKbeta in August 2018, two Norwegian daily news podcasts have surfaced, both sharing characteristics with The Daily (and another favourite; Today Explained from Vox). We live in exciting times.